When I started researching my family history, my main aim was to learn more about my dad’s early life and find out about my grandparents.

In the process, I began to realise just how many lives are attached to my family tree. Each branch that I looked at uncovered long-forgotten great aunts and uncles and distant cousins. I decided there were just too many for me to investigate fully, so I decided I would set them aside and come back to them later.

However, one name caught my attention right from the start, Clark Thomson. Initially, I was intrigued by the name. Clark is not a common first name in Scotland. I wondered why I wasn’t aware that my Dad had an Uncle Clark. Surely, I would have remembered hearing that name. I found myself wondering where it had come from and why no one seemed to have heard of him.

As I looked more closely at Clark, I found his story both interesting and poignant. It brought to light a feature of the First World War which I had not considered before, the role of the Royal Medical Corps.

It also revealed a possible solution to the mystery of why no one seemed to know about him.

In the end, I was glad I took a closer look at Clark. Here is his story.

Clark Thomson was born on the 3rd of September 1891, at 10 India Street, Rutherglen. His parents were Archibald Thomson, a potter, and Agnes Simpson. I believe Clark was named after his paternal grandmother, Mary Clark.

He appears in the 1901 Census living at 15 Mitchell Street, Rutherglen with his parents and siblings. At the age of 9, he was the second youngest child. His brother, Thomas, my grandfather, was three years younger.

In the 1911 Census, he is recorded as residing with the family at 16 Stonelaw Road. This Census entry reveals that Clark, and his older brother, Peter, were both potters. They would have worked beside their father in the Caledonia Pottery in Rutherglen. Clark was 19 years old.

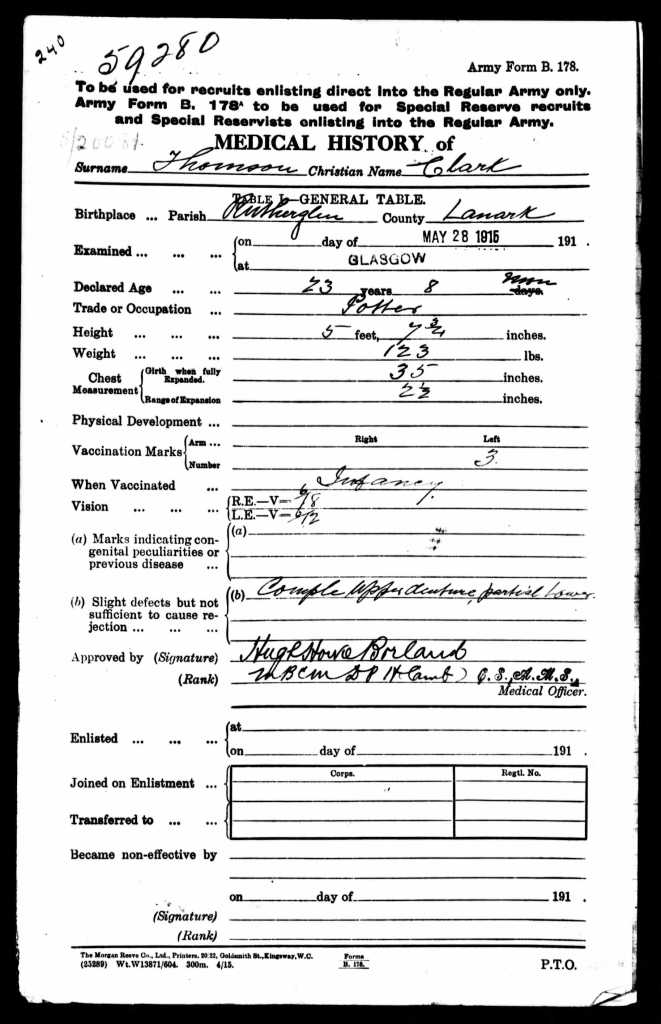

It seems Clark was a slightly built young man. He was 5’7” and weighed only 123 lbs or 55.7 kg.

When war broke out in 1914, Clark’s younger brother, Tommy, was enlisted and departed in 1915 with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

At first, I wondered why Clark, who was three years older than Tommy, was not also recruited at the outset of the war. Then, I realised that he had an upper denture and a partial lower denture. For a young man, this indicated that he had bad dental problems.

Most people at the end of the 19th Century could not afford dental treatment and I discovered that at the outbreak of war many men were being rejected for recruitment due to deficient teeth.

It was soon realised that many of these men would otherwise not have been rejected. The British Dental Association and the Scottish Dentists’ Association volunteered to treat these men if treatment would make them fit for service. By January 1915, any man with defective teeth could be attested if he were otherwise fit and was willing to get dental treatment.

Often this dental work would be carried out by civil dentist many of whom were unqualified. This resulted in many men having their teeth removed unnecessarily. They would then have to wait until their mouths had recovered enough for them to be fitted with dentures.

As Clark was not recruited until April 1915, I believe the delay may have been because he was having this dental work carried out.

Eventually, however, he became Private S/20081 with the Argyll and Southern Highlanders on 26th April 1915. He was immediately sent to Malta where he spent 9 days before being transferred to the Royal Army Medical Corps as Private 59280.

The RAMC was a non-combatant branch of the Armed Forces. Although they were sometimes given weapons, they could only be used for self-defence under exceptional situations.

WW1 was the first war in which it was fully realised that a soldier’s chance of survival depended on how quickly his wound was treated. The use of heavy artillery and machine guns was resulting in vast numbers of casualties, all needing treatment at the same time. Doctors could not perform efficiently on the front line, and efficient transportation of casualties to places where they could be treated more effectively was critical. Of course, the main aim of the entire process was to treat soldiers and return them to the front line as quickly as possible.

As the war progressed, this complex system of mobile treatment stations with its web of transportation became known as the ‘Chain of Evacuation’. The RAMC was to play a significant role in the war by providing quick and efficient triage, emergency first aid, and crucial treatment.

Before any major offensive, the Medical Services planned how the Chain would be implemented. The process was complex. It involved front line medical field units that could move at a moment’s notice. These were made up of Regimental Aid Posts that moved forward with the fighting. The key role of the RAP was to patch up the wounded and return them to duties at the front line. If this were not possible, they would be sent back to the Field Ambulance. Stretcher-bearers would then collect the sick and wounded and take them to the Advanced Dressing Stations. The ADS would provide immediate emergency treatment, assess patients to make sure bandages were adequate and that they weren’t haemorrhaging or going into shock.

The casualties would then be transported to the Main Dressing Station, before going to the Casualty Clearing Station. The CCS was where they could be stabilised, x rayed, prepared for operation, or receive treatment. The main aim of the CCS was to treat casualties and move them on as quickly as possible.

If deemed necessary, the casualty would be taken to a base hospital. Once at the base hospital, the casualty would stay to recuperate or, if too severely injured, would be carried by hospital ship back to Britain.

The men and woman who served in the RAMC played a vital role in maintaining this intricate system of moving and treating the wounded amid bloody and dangerous battles. There was a wide range of jobs involved in the Chain of Evacuation. Staff included doctors and surgeons, nurses, and anaesthetists, as well as an army of stretcher-bearers, orderlies, technicians, and transport workers. Transportation of the injured was carried out by a combination of people, horse and cart, and later on by motorised ambulances, trains and boats.

In Malta, Clark joined the hospital ship, The Glengorm Castle.

The Glengorm Castle was built in Ireland by Harland and Wolff and was originally named The German. She had served as a trooping ship in the Boer War. In August 1914, she was commissioned as Hospital Ship and being renamed. By September 1914, she had been refitted with 423 beds.

Clark spent two years aboard the Glengorm Castle. I do not know what his role was aboard the ship, but it is most likely he was an orderly. He would have been involved in receiving and treating the injured who arrived daily from the fighting taking place in Gallipoli and Salonika.

The photos above are copied from an Album collated by 22/74 Sister Mary Eleanor Gould, New Zealand Army Nursing Service Corps. The album covers Sister Gould’s time in Egypt on the Marquette, HS Gascon, HS Glengorm Castle and in England. I have enhanced the photos for clarity and colour.

The Album can be viewed on New Zealand’s National Army Museum Recollect site. https://nam.recollect.co.nz/

In July 1917, Clark left the ship and was transferred to the land-based units serving with the Salonika Campaign.

He spent the next two years with the RAMC supporting the soldiers fighting at the Greece-Macedonia border. Even after the war ended, in November 1918, Clark continued his service in Salonika until he contracted Malaria.

Malaria had become an unforeseen foe during WW1, infecting at least 1.5 million soldiers and killing thousands. The illness caused nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea and could leave men suffering from jaundice and serious recurrent fevers. The outbreak of Malaria in Macedonia was so bad it immobilised whole armies on all sides for months.

Clark was examined in Bulgaria, before being discharged from the army on the 26th April 1919. He had served almost four years. He was awarded a war pension of 5/6d for a year. He would have received the War Medal and Victory Medal for his service.

After his discharge, Clark returned to his father’s home at 16 Stonelaw Road and found work with his previous employer, The Caledonian Pottery as a Pottery Turner.

Shortly after his discharge, Clark’s mother, Agnes, died from a heart condition. His brother, Tommy, had returned from the Western Front the year before but had since married and was no longer living at the address.

Clark was now 28 years old. He soon met a young woman named Jessie McDonald, and they became betrothed. Jessie, a worker in the carpet mill, was three years younger than Clark. She seems to have been previously married to a man called Aitken.

Clark and Jessie were married on the 29th October 1920, at 16 Stonelaw Road. The ceremony was performed by a minister from the Church of Scotland.

It was probably convenient for the newly married couple to remain at the house, to support his widowed father, Archibald.

Archibald himself died in 1928, and Clark registered his death before taking over the tenancy of the flat.

In 1929, the Caledonian Pot Work closed, and, at some point, Clark found new employment in the dye works. The 1940 valuation roll for 16 Stonelaw Road suggests he was still a potter, but I don’t know where he would have been working at that time.

In the early 1950s, my parents moved into a flat in the same close as Clark and Jessie. I believe Clark had already been admitted to hospital by this time as my mum had no idea of his existence.

He had Pulmonary Tuberculosis the most common form which would have given him a life expectancy of about 5 years. The stigma attached to this condition might explain his mysterious disappearance and the silence surrounding him at this time.

In 1948, someone was dying from this illness every 2 hours. Long considered a disease of the lower classes it was thought to be a ‘dirty’ disease. This perception was exacerbated by the symptoms of the disease the awful cough which often produced blood. It was also recognised that careless spitting, sneezing, and coughing around others spread the illness.

Yet no family, rich or poor, was immune to this disease. A diagnosis of ‘consumption’, as it was commonly known was, in effect, a death sentence.

The treatment of the disease with drugs in the 1950s was still in its infancy and confinement in sanitoriums was still a common occurrence. It had long been believed that fresh air was beneficial for TB sufferers. A practice which also effectively hid the TB patient from society.

Sun parlour in a tubercular hospital in Dayton, Ohio 1910-1920. Library of Congress

Clark had been admitted to the Roadmeetings Hospital in Carluke. This hospital which had opened in 1928 was dedicated to infectious disease and had 26 TB beds. The single‑storey wards had south facing verandas where the patients could be taken out to enjoy the fresh air.

Despite the introduction of the new drug Streptomycin, Clark died at the hospital on the 11th Feb 1957. Jessie registered his death at Law the next day.

Jessie continued to live at the flat after his death.

I have wondered why my mum couldn’t tell me anything about Clark and Jessie. After all, she had been their close neighbour for several years in the 1950s. She had no recollection at all of Clark and didn’t even recognise the name. I did find this strange as he died in 1957 whilst my parents were living in the same close.

Of course, Mum had not long been married at the time. She had two very young children and was expecting her third baby who was born in May 1957. She was probably too busy, or at least too distracted, to pay much attention to my Dad’s elderly aunt. However, I believe that the fact that Clark was a TB patient was the main reason she didn’t know about him. Could the family have been embarrassed by his illness? This might explain why no one knew anything about him.

Mum did remember Dad’s Wee Auntie Jessie, who continued to live at Stonelaw Road after Clark’s death. She described her as being very small and reserved. She always wore a hat and went to church on Sunday. She also revealed that Jessie appears to have had a bit of a drinking problem as she was once found lying in the back outhouse completely drunk!

Maybe this should have been no surprise, as she was covering up a deep secret!

I hope you have enjoyed reading about my Uncle Clark. I have used my imagination to fill in the gaps in his story. Of course, I may never know exactly what his role was in the RAMC or why he seemed to have disappeared from our family. They are just my interpretation of the facts. If you have other ideas, why not let me know.

Sadly, I have no photos of Clark or Jessie. Maybe someday I’ll come across some.

Very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Joe said very good as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember my Dad’s auntie Jessie. We used to go down the stairs to see her. Really old wee lady. She had a tin full of knitted baby bootees. Dont know why I remember that. Dont remember the name Clark though. We didnt see much of her though but I think my Dad went in to see her more than the rest off us. Dont think my Mum liked us going down to see her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! Great in investigating, Elizabeth!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on The Chiddicks Family Tree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great story Liz, I had no idea so many were lost to Malaria during the War. We are so blessed now that we have vaccinations and cures for these infectious diseases.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting and sad. Good history lesson.

LikeLike

Thank you. Yes, a sad tale.

LikeLike